The Union Jack is slowly lowered. An enormous clamour rising from across Salisbury’s Rufaro stadium hits fever pitch as 36 000 people celebrate the hoisting of the new green-gold-red-black-white flag, marked with a star and a Zimbabwe bird, symbols of the new state.

The crowd roars to a 21-gun salute. The din of planes fills the night sky. The applause and cries of joy gradually subside and the singing starts.

It is shortly after midnight on Friday, April 18, 1980. Zimbabwe has just been born.

Ninety years of colonisation is brought to an end with Britain’s granting of independence to its former rebel colony.

In front of the excited crowd, the heir to the British throne, Prince Charles, hands the text of the constitution to the president of the new state, Canaan Banana, in a symbolic transfer of power.

There are 100 foreign delegations in the official stands.

Apartheid South Africa and most of the countries of communist Eastern Europe are not represented.

However the continent’s main liberation movements – including those of South Africa, the Polisario Front of the Western Sahara, and the Palestine Liberation Organisation – are in attendance, alongside Western countries.

Notably absent is the former leader of rebel Rhodesia, Ian Smith.

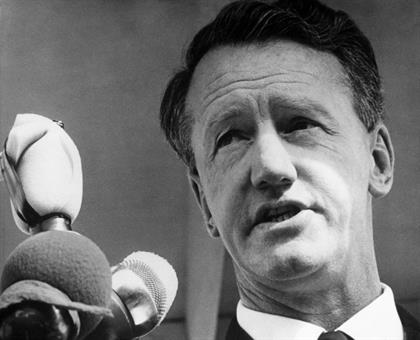

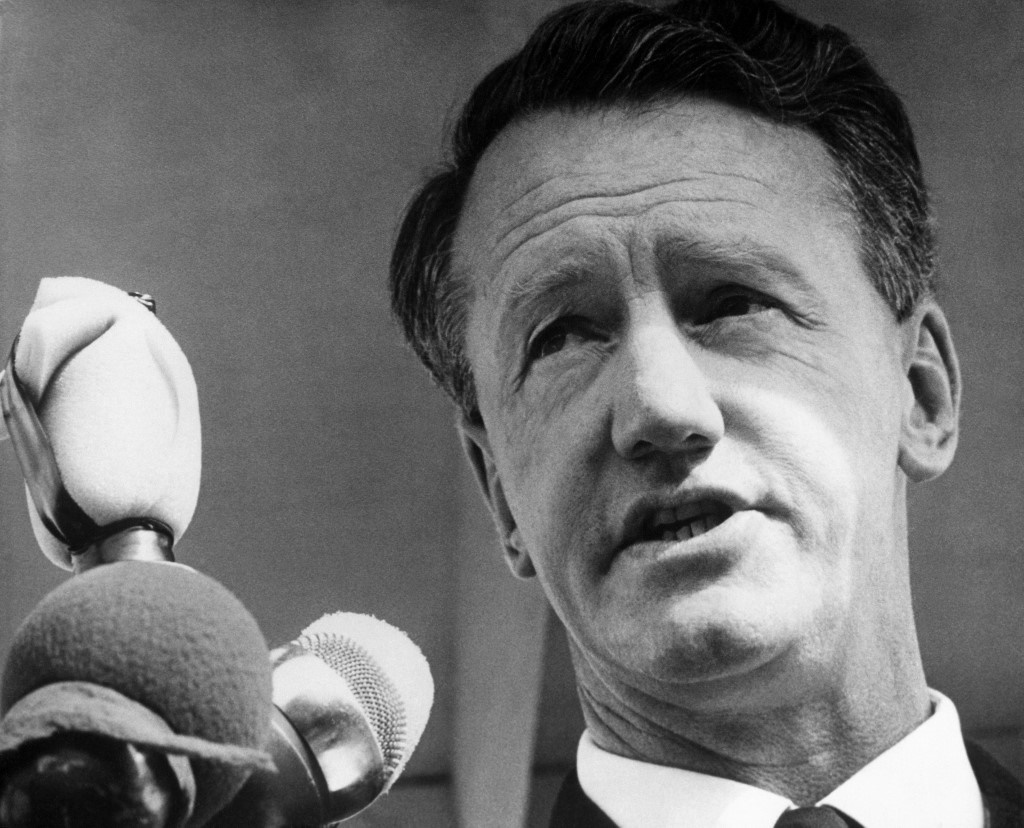

Smith had on November 11, 1965 also declared independence, but unilaterally and against the wishes of London.

It was the first time a British Crown colony had broken away since the United States in July 1776.

His Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) led to a 15-year dispute with London during which black nationalists launched a guerrilla war against the white regime in Salisbury, today’s Harare.

Smith made the bold move to put an end to long independence negotiations with Britain and to prevent blacks – who numbered six million against the white population of 250 000 – from coming to power.

Previously the colony of Southern Rhodesia, the rebel country took the name Rhodesia, after British explorer Cecil Rhodes who claimed the region on behalf of the Crown in the late 19th century.

It was immediately condemned by African and foreign states.

Internationally isolated and under British and UN sanctions, Smith’s regime soon had links only with South Africa and Portugal and its colonies.

London believed it would eventually cave in under the pressure. But it underestimated the determination of Rhodesia’s whites who benefited from an abundant reserve of black manpower to build a self-sufficient and prosperous nation.

From the mid-1960s Rhodesia was faced with insurrection.

The decisive phase in the conflict came at dawn on December 21, 1972 when a small commando launched a rocket attack on a white-owned farm in the northeastern locality of Centenary.

A girl was wounded and windows broken, and the white community saw it as a one-off incident.

It turned out to be the start of seven years of conflict called the Bush War, which would leave more than 27 000 dead. The guerrilla force strengthened from year to year and clashes intensified, especially after neighbouring Mozambique obtained independence in 1975.

However the black movement was divided, with rivalry developing between the ZAPU (Zimbabwe African People’s Union) faction led by Joshua Nkomo and Robert Mugabe’s ZANU (Zimbabwe African National Union).

While both followed a socialist ideology, the more moderate ZAPU wanted negotiations with the authorities for a transfer of power.

ZANU was more radical, favouring armed struggle.

A third player was the United African National Council of Methodist Bishop Abel Muzorewa, which rejected violence while demanding “one man, one vote”.

Amid the infighting, Mugabe emerged by 1976 as the leader of the overall 12 000-strong guerrilla movement.

Under pressure from the escalating war and waning support from Portugal and South Africa, Smith opened negotiations on a transfer of power.

The white regime met with black nationalists for a first time on August 25, 1975 in a train on a bridge over Victoria Falls bordering Zambia after demands for a venue on neutral territory.

While that first meeting failed, it launched a process that culminated in a 1978 agreement on a political transition.

In April 1979 elections were held for the 100-seat parliament with a majority of seats allotted to blacks, but some still guaranteed for whites.

Muzorewa’s party won and he became prime minister of the state of Zimbabwe-Rhodesia, proclaimed in June 1979.

White minority rule had ended.

But the guerrillas did not halt their insurgency and the new nation was also rejected on the world stage.

Britain called Muzowera and nationalist leaders including Mugabe and Nkomo to talks on reaching internationally recognised independence, reaching on December 21 the Lancaster House Agreement, named after the venue of the talks.

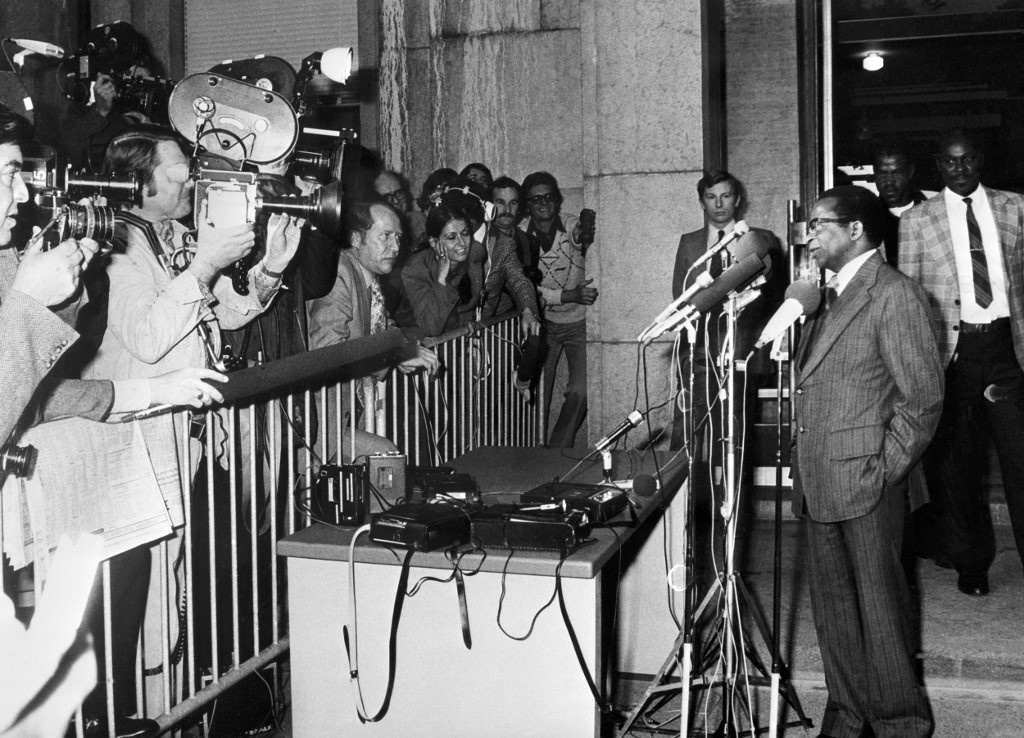

1980 elections were won by Mugabe, who became prime minister and then president.

He first won praise for his policy of reconciliation but went on to set up an authoritarian regime which brutally repressed opponents and implemented a land reform programme that resulted in economic collapse.

Forced to resign in 2017, aged 93, and after 37 years in power, Mugabe died two years later

His successor Emmerson Mnangagwa has promised to fight corruption, revive the moribund economy and reduce poverty.