Moves by rich countries to buy large quantities of monkeypox vaccine, while declining to share doses with Africa, could leave millions of people unprotected against a more dangerous version of the disease and risk continued spillovers of the virus into humans, public health officials are warning.

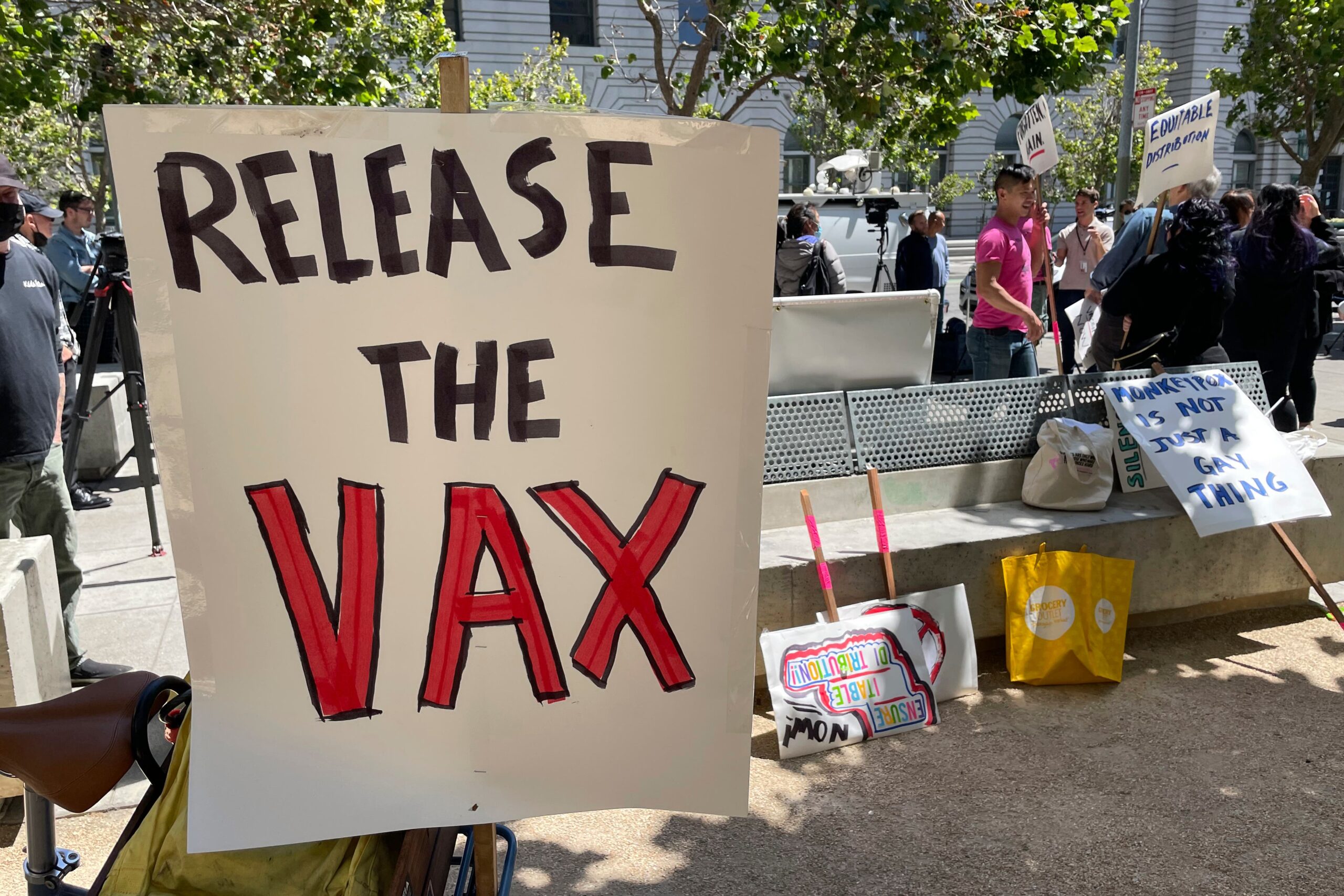

Critics fear a repeat of the catastrophic inequity problems seen during the coronavirus pandemic.

“The mistakes we saw during the COVID-19 pandemic are already being repeated,” said Dr. Boghuma Kabisen Titanji, an assistant professor of medicine at Emory University.

While rich countries have ordered millions of vaccines to stop monkeypox within their borders, none have announced plans to share doses with Africa, where a more lethal form of monkeypox is spreading than in the West.

To date, there have been more than 21,000 monkeypox cases reported in nearly 80 countries since May, with about 75 suspected deaths in Africa, mostly in Nigeria and Congo. On Friday, Brazil and Spain reported deaths linked to monkeypox, the first reported outside Africa.

“The African countries dealing with monkeypox outbreaks for decades have been relegated to a footnote in conversations about the global response,” Titanji said.

Scientists say that unlike campaigns to stop COVID-19, mass vaccination against monkeypox won’t be necessary. They think targeted use of the available doses, along with other measures, could shut down the expanding epidemics recently designated by the World Health Organization as a global emergency.

Yet while monkeypox is much harder to spread than COVID-19, experts warn that if the disease spills over into general populations — currently in Europe and North America it is circulating almost exclusively among gay and bisexual men — the need for vaccines could intensify, especially if the virus becomes entrenched in new regions.

On Thursday, the Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention called for the continent to be prioritized for vaccines, saying it was again being left behind.

“If we’re not safe, the rest of the world is not safe,” said Africa CDC’s acting director, Ahmed Ogwell.

Although it has been endemic in parts of Africa for decades, monkeypox mostly jumps into people from infected wild animals and has not typically spread very far beyond the continent.

Experts suspect the monkeypox outbreaks in North America and Europe may have originated in Africa long before the disease started spreading via sex at two raves in Spain and Belgium. Currently, more than 70% of the world’s monkeypox cases are in Europe, and 98% of cases are in men who have sex with men.

WHO is developing a vaccine-sharing mechanism for affected countries, but has released few details about how it might work. The U.N. health agency has made no guarantees about prioritizing poor countries in Africa, saying only that vaccines would be dispensed based on epidemiological need.

Some experts worry the mechanism could duplicate the problems seen with COVAX, created by WHO and partners in 2020 to try to ensure poorer countries would get COVID-19 shots. That missed repeated targets to share vaccines with poorer nations and at times relied on donations.

“Just asking countries to share is not going to be enough,” said Sharmila Shetty, a vaccines adviser for Medecins Sans Frontieres. “The longer monkeypox circulates, the greater chances it could get into new animal reservoirs or spread to” the human general population, she said. “If that happens, vaccine needs could change substantially.”

At the moment, there is only one producer of the most advanced monkeypox vaccine: the Danish company Bavarian Nordic. Its production capacity this year is about 30 million doses, with about 16 million vaccines available now.

In May, Bavarian Nordic asked the U.S. to release more than 215,000 doses it was due to receive, “to assist with international requests the company was receiving,” and the U.S. complied, according to Bill Hall, a spokesman for the department of Health and Human Services. The U.S. will still receive the doses, but at a later date.

The company declined to specify which countries it was allocating doses for.

Hall said the U.S. has not made any other promises to share vaccines. The U.S. has ordered by far the most number of doses, with 13 million reserved, although only about 1.4 million have been delivered.

Some African officials said it would be wise to stockpile some doses on the continent, especially given the difficulties Western countries were having stopping monkeypox.

“I really didn’t think this would spread very far because monkeypox does not spread like COVID,” said Salim Abdool Karim, an infectious diseases epidemiologist at the University of KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa. “Africa should procure some vaccines in case we need them, but we should prioritize diagnostics and surveillance so we know who to target,” he said. “Normally, you’re able to get ahead of a disease like monkeypox, but I am concerned (the number of new cases) hasn’t started coming down yet.”

Dr. Ingrid Katz, a global health expert at Harvard University, said the monkeypox epidemics were “potentially manageable” if the limited vaccines were distributed appropriately. She believed it was still possible to prevent monkeypox from turning into a pandemic, but that “we need to be thoughtful in our prevention strategies and rapid in our response.”

In Spain, which has Europe’s biggest monkeypox outbreak, demand for vaccines far exceeds supply.

“There is a real gap between the number of vaccines that we currently have available and the people who could benefit,” said Pep Coll, a medical director at a Barcelona health center that was dispensing shots this week.

Daniel Rofin, 41, was more than happy to be offered a dose recently. He said he decided to get vaccinated for the same reasons he was immunized against COVID-19.

“I feel reassured it is a way to stop the spread,” he said. “We (gay men) are a group at risk.”

___

Joseph Wilson and Renata Brito in Barcelona, Spain, Chris Megerian in Washington and Cara Anna in Nairobi, Kenya contributed to this report.