Tomorrow marks the 57th anniversary of the founding of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU).

In May of 1963, 30 heads of African states and governments that had attained liberation not long before assembled in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, where they endorsed what was to be the OAU Charter, one of whose objectives was to coordinate and intensify efforts to achieve a better life for the people of Africa.

The history-laden continental body was, in 2002, reconfigured and birthed the current African Union (AU).

But to what extent can we say that the setting up of this organisation has brought relief to the long-suffering masses across the continent?

For a proper appraisal and assessment of the performance of the organisation, it will be prudent to divide the 57-year timeframe into two: the first 25 years and the latter 32 years.

It is no exaggeration to suggest that the earlier years of the OAU’s existence were characterised by a complete failure on its part.

Granted, it was through its lobbying efforts and pressure that the granting of independence to those countries still under colonial rule picked up pace, including in South Africa’s case.

Corruption has always been a major problem. One of the reasons that largely led to seizure of power was the desire to sit at the table where money exchanged hands. And this is the privilege mostly enjoyed by a head of state

Collin Nxumalo

But that is as much as can be said regarding accomplishments during this period.

Not only was the organisation missing in action where it was expected to have been involved, for example, ensuring that there were minimal instances of the removal of governments by the army and that there were no unnecessary killings and maiming of innocent people, but there were several instances where the very annual summits of the organisation provided opportunities for disgruntled opposition members (and the army) of member states to stage coups against their governments back home when the head of state was away at the OAU meeting.

In the same year it was constituted, three governments fell to coups: Dahomey/Benin, Congo-Brazzaville and Togo, and in all instances armies were involved. It is safe to say that during the OAU’s life span, the continent was beset by strife and bloodshed.

Between 1963 and 1969, 25 military coups took place on African soil.

Almost all the countries that got their independence before 1980 were at one stage or another forced to deal with internal strife and the resultant civilian casualties.

Arguably the only exceptions to this anomaly would be Botswana (a beacon of stability on the continent), Malawi, Senegal, Swaziland (now Eswatini) and Zambia.

Kenya and Tanzania did face a mutiny from their armies, but in both cases this was quickly put down with the help of British troops. But then again, it was not only strife and coups that galled the masses of the continent.

Corruption has always been a major problem. One of the reasons that largely led to seizure of power was the desire to sit at the table where money exchanged hands. And this is the privilege mostly enjoyed by a head of state.

This much was demonstrated by Michela Wrong in her book, It’s Our Turn to Eat: The Story of a Kenyan Whistle-Blower, published in 2010.

Although her main focus was about the shenanigans within Kenyan politics, what was happening there captured the modus operandi of how African politics was conducted.

The extent of failure by African governments to provide for the needs of their people is illustrated by the trend of the political elite’s choosing to go abroad for medical attention, rather than using their local medical facilities. Generally, they did not improve facilities and life at home.

There was a time when South Africans confidently asserted that “this country is different. It will not go the way of countries north of the Limpopo.”

Former president Thabo Mbeki often references what he says is a refrain he encounters whenever he travels abroad: “What went wrong with South Africa?” people would ask him.

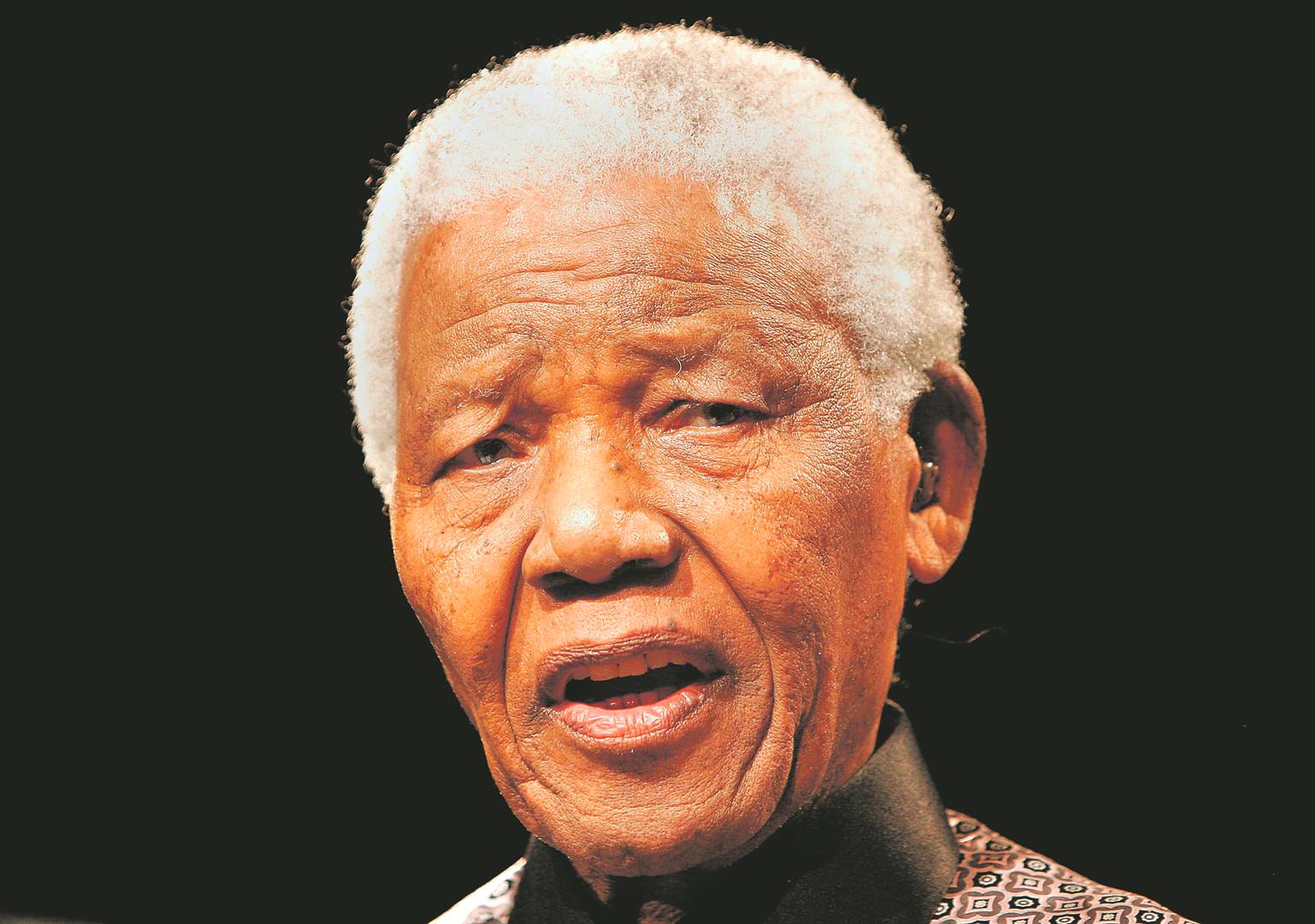

The question is based on the hopes that the international community had placed on the country following its attainment of freedom in 1994. At the time, with iconic Nelson Mandela at the helm, nothing could go wrong.

The excitement of being free at last clouded our vision for the future. Somehow we failed to recognise that a Mandela was not going to be there forever.

It was a matter of a couple of years after his stepping down, when everything and anything that could go south, indeed went south (excuse the pun).

A lot still has to be done, such as assisting fraternal countries develop their economies to a level where they can create opportunities and offer jobs to locals

Collin Nxumalo

Yet the sun is rising anew, with all the promise of a brighter and energy-filled era. The current African leadership gives us a sense of hope.

The guns have been silenced, and the effort is holding. There are consequences for those transgressing the protocols of the AU Charter that calls for the expulsion of governments that assume power through means other than democratic processes.

An increased number of countries have signed the free trade agreement, which will make it easier to do business across borders. It is hoped that, with time, all will sign.

A lot still has to be done, such as assisting fraternal countries develop their economies to a level where they can create opportunities and offer jobs to locals.

And that will (hopefully) solve the burden experienced by a few countries that find themselves having to shoulder an influx of people unable to make a living in their native countries.

And when people migrate to other places in search of the means to make a living, there will always be the risk and danger of invoking the fires of xenophobia, something that must be avoided at all costs.

Nxumalo is a writer and head of Concept Africa Research Group